Playfully elegant whilst intoxicatingly sultry, Alfie creates stop frame animations of the female form, beautifully choreographed and composed with an underlined sense of nostalgia. This age old technique enables her to create a visual world of illusion where her subjects extrovertly prance through her make believe stage sets. Alfie’s films touch on the burlesque and cheekily cross the boundaries between art, theatre and fashion. Following in the footsteps of Leigh Bowery and David LaChapelle, her work is encapsulating, fun and gregarious.

There is a love in Alfie’s work, of possibilities, In each of her films she explores, the many ways a person can look, a metamorphosis of appearances, with the aid of costume, body art and movement. Her figures are like chameleons, constantly changing shape, colour and form. Presented with a panorama of characters in her work, we can wonder, in the same way we may view Cindy Sherman photographs, at the many different ways a woman can project herself. But unlike Sherman, Alfie’s work concentrates solely on positive projections, unswayed by the modern anti-aesthetic photography.

In the Exsertus space Alfie invites us to explore a series of experimental films working with professional dancer, the fabulous Georgie Leahy.

James Johnson-Perkins

The day approaches three o’clock. A library of records leans against a partition, dust is caught beneath a wall’s white emulsion. Thomas gesticulates. He wants to talk about notions of quality within art. Thomas claims he led him to this point. There is a smile. Somewhere outside the gallery, footsteps can be heard.

This is not work, Walker tells Thomas.

Next to a false wall is a brown box containing materials for a previous project; the box has been opened but remains full. Walker’s previous installation had been cancelled after one day. He spent four months working on it. Thomas asks for the name of the new project. Therapy, Walker replies.

By the door are eight paintpots, arranged in two stacks. There are also two tables in the room. It appears that Walker uses one for writing and one for painting. Thomas looks away but cannot avoid looking at the two words on the wall. It is not always possible to talk about what it is that one is seeking to recover from.

A ladder holds its place near to the entrance. Elsewhere, various everyday objects are scattered throughout the workplace. Some look as though they have been broken, others look as though have been fixed. An office chair with wheels waits invitingly in the centre of the room. This is not work.

Some people feel that art and life inform each other. Thomas looks at the uncut logs set upon easy circles of woodchips and splinters, he looks at the keyboard, the marinucci organ and the xylophone. In the corners of the space, uneven grey floorpaint curls at the edges. He looks at the words on the wall once more, he cannot fathom why. Here, somewhere, there is an interest in etymology and slippages of meaning. Thomas sits on a red chair.

What is that blanket for, Thomas asks. Security, Walker replies.

Audiences are detectives, readers are operatives. In exploring the relationship they have with their own art, artists question the autonomy of meaning. Thomas looks once more at the two words on the wall, questioning. There are slow rewards here. Justification, fulfilment, finality; all are sought and seldom found. Yet still we look. The typewriter and paper, seemingly the focal point of the room but not always noticeable, sits on the table. The paper is blank.

This is not yet work, Walker says. This is the beginning of the work, the start of a tangent from itself. This is not work. Footsteps can be heard again from outside.

Thomas looks to the two words on the wall and understands. They are over ten feet high.

Adam Thomas

At first view Andrew Burton's new work in the Exsertus space plays with your sense of scale. The work is a wall constructed from thousands of fired bricks dividing the space into two. The bricks however are finger sized, a kind of lego-like miniature construction block from which Burton has built a wall that would be well over head height if normal sized construction bricks were used.

The wall structure gives the sense of creating a boundary, or in a space that lies along the route of Hadrian's wall, a frontier. In stepping over the barrier and viewing the work from the far side of the space, we can see that the wall has been filled with street tags, but due to tiny size of the bricks and the scale of the wall, the graffiti writing is of a miniature scale.

Burton's inspiration for working with fired bricks came from the experience of working in India, and observing what at first appeared to be piles of discarded bricks, but were actually the product of local brick yards. These piles of bricks had an order to them, and could be found all over India, an example of the staple Indian building material. The chances of seeing these discarded bricks may become a rarity, as the Indian government moves towards financing large-scale construction from concrete and more modern building materials.

This piece, constructed in the Exsertus space is one of a number of works that Burton has constructed from the same bricks. Here they have taken on a life of their own as they are reused in successive sculptures, bringing with them remnants of the paint and glaze from the works that have gone before.

Bricks are a universal material for construction, and they are found worldwide. Their versatility as a method of construction lend themselves to forms that are solid and permanent. Bricks give us a sense of solidity and comfort that they will not fall down. Burton's piece is neither solid nor permanent. Its precarious nature invites danger in the simple act of stepping over it. The precariousness of the construction reflects the precarious nature of the area that Harker's building is situated. Industrial buildings are being levelled on virtually all sides reminding us that the Exsertus space itself, like the Harker’s Building is only a temporary home for artists.

Matthew Cowan

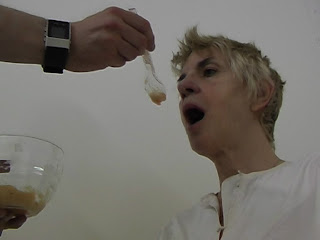

With Johnson’s work the audience is forced to re-appraise her uncanny props, which often portray elements of decay, regurgitation and waste. Her work is undeniably influenced by gothic horror and science fiction and tips its' hat to James Herbert, Franz Kafka, H.P. Lovecraft and films such as Alien and The Thing. Her work also has similarities with artists such as Mike Nelson, Ilya Kabakov, Lynda Bengis, Cindy Sherman and Gavin Turk, in that her practice investigates abject states between reality and fiction.

Kathryn Johnson likes to instigate people's natural curiosity and to stimulate their imagination, creating sculptural scenarios which have multiple interpretations. The dazzling effect of her work is that we are offered the chance to indulge ourselves in creating our own fantastic stories and reasons to understand her faux hallucinogenic, bizarre and surreal panoramas.

James Johnson-Perkins

The Polynesian spiritual concept of tapu governs many aspects of sacred and everyday life, in particular food its consumption. In some situations designated members of society, as sacred practicitioners are unable to feed themselves because they are in a state of absolute tapu, and to touch the food itself would represent a transgression of their tapu state. They have to be fed in a special way, so as not to contaminate the food by touching it themselves. It elevates the status of the food itself as a sacred object.

The atmosphere in the performance space here too is one of a sacred realm, with sheets of paper containing fragments of writing - spanning a large central circle in the middle of the space. These pieces of writing are not literal or concise but hint at the elements of the performance in which they are a part of. Some contain text from Carole’s weblog, a parallel ingredient to the performance. The words describe her time, removed from everyday life, in the space as being a kind of retreat, drawing from the monastic traditions of solitude and contemplation, but with a focus on hunger. Arranged in the circular shape they map a well-trodden path over the course of the residency.

Matthew Cowan

“I am going; I’m going away; I’ll be away for a few days, away for some time; I’m going away from everyday life; there will be a time for you to visit if you wish. I invite you to visit I invite you to visit me if you wish I invite you to visit me in my place my place away you can come visit me if you wish.”

Carole Luby

Set in the Novellus Castellum gallery space Exertus, Matt Fleming fills the space with old cameras, projectors, monitors, he creates a sort-of-ghost-like landscape of stuff. The sputtering, whirring almost attic like detritus might remind you of the unravelled psyche of some obsessive and unworldly geek but its much more than this. Memories of childhood peep out against the broken, static hiss of a deranged television studio camera, while a slide-projector ‘ca-chunks’ violently somewhere in a dimly lit corner.

On an entrance wall are records of Matt Fleming’s ideas on the installation. It alludes to notions of Irony and melancholy. Melancholia can often be read as a metaphor for the mind's collapse. This is where Fleming toy’s with us as his experiments, his machines collapse and spit their parts out at us. His machines are challenging us, mocking us and prodding us to find a meaning in something that is, associated with the twee, the post-adolescent and the nerdy. Its Tinguelyesque art brut mixed with a subtle pinch of Takahashi spice topped with Gondrylike garnish for the digital age all finished off with a rye smile. You could mistake this for real chaos, and the yet the post-modern ethos of chaos is seen as no longer original. Fleming’s success is that the layout of the space functions very much like a Dutch still life. Hence the originality lies within deciphering the externally and internally complex language and the organised chaos of this machine-like landscape laden rich in its jokes, puns and wise cracks all cleverly hidden and sub-verted for our pleasure.

Richard A. Phipps

Mat Fleming presented a series of experiments in 35mm film, 16mm film and video, which developed through his residency at the Exsertus project space. A cacophony of machines and films, amongst other things, attempt to deconstruct the process of translating 35mm photography into film; reverse engineer the pixel; and reveal the sculptural mechanics of the process.

Ele Carpenter

“The aim of the show is to create something of beauty. I think beauty is truth, keeping in mind 3 things: that one shouldn't take oneself too seriously, that truth is stranger than fiction and that something should be true to its own trickery. Like Godard said: cinema is "reality 24 times a second".

My show of work produced experimentally over the last month hopefully embraces that contradiction and my own limitations working like an artisan in an industrial medium.

I am hopefully turning failed science into good art and presenting new entertaining film installations in progress.”

Mat Fleming

[Collaboration on 35mm film with Chris Bate]